Mary Lee Brady, Ph.D.

| |

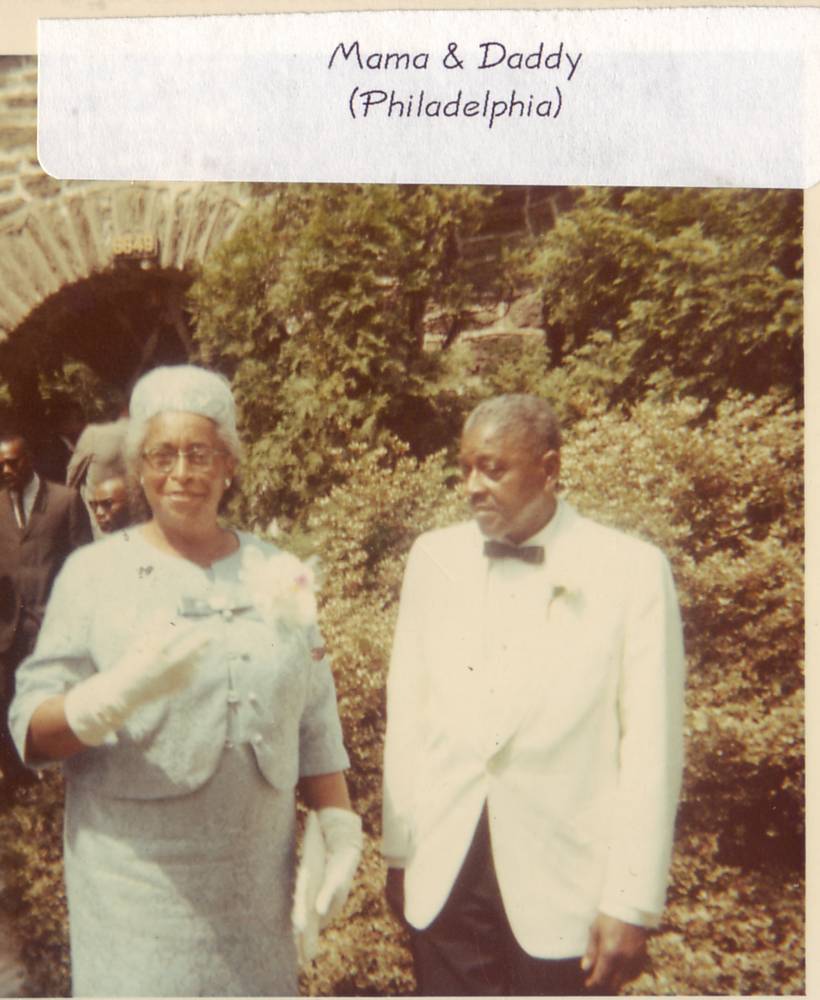

William Thomas Atkins, son of Luther Adkins/Atkins and his wife Julia Kyle Atkins was born Dec 17, 1906 in Salem, Virginia in a house and on land referred to as Ash-Bottom owned by his maternal grand-father Charles Kyle and grand-mother Adaline Frogg Kyle. He died in January 1993 having lived 87 years through tumultuous years of labor hardships, opportunities and strife during eras of World War I (1914-1918), World Depression (1929-1939), World War II (1937-1945), Korean War (1950-1954), Vietnam War (1963-1975) and the First Gulf War (1990-1991).

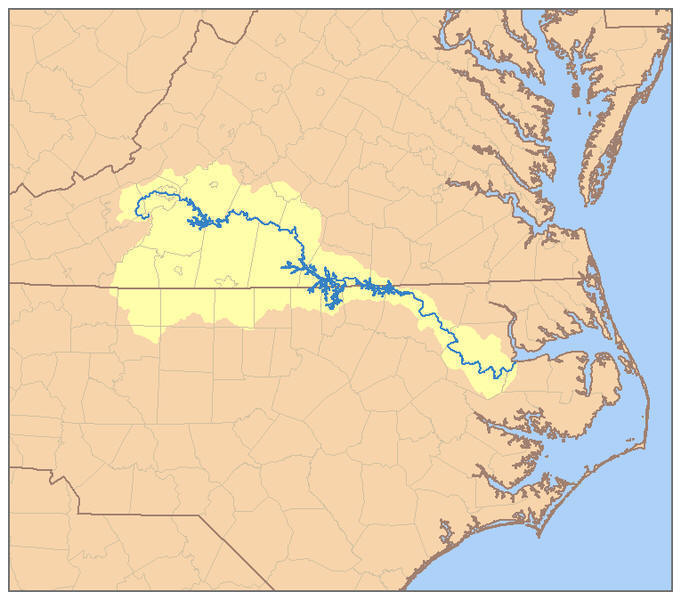

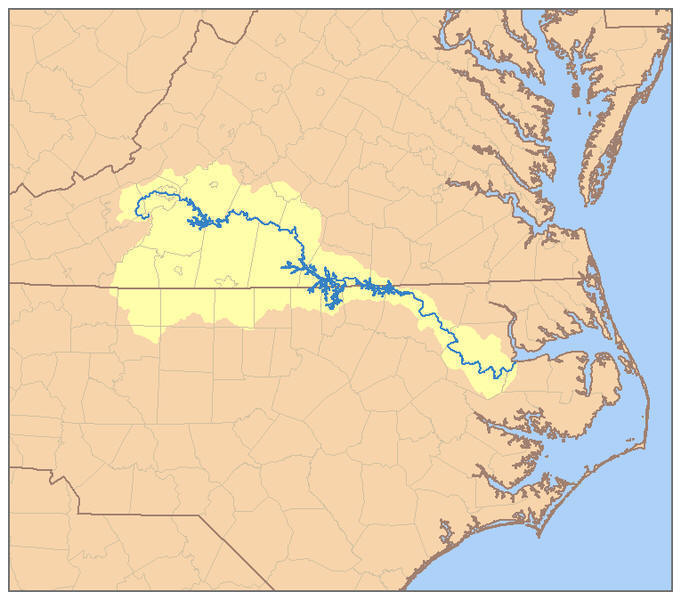

William Thomas Atkins Story William believed his birth mark was a reminder from his grandfather's genes that freedom was not free. And, living as a freeman required courage to acquire and sustain it in the face of many who wished he did not have it and others who think the Black man as unworthy of freedom. For William, his story of heroes began with: 1. Great-grandfather Thomas Kyle who was chained and sold down-river to Mississippi because he dared encourage his sons and nephews to escape slavery and join the Union forces fighting to free them. 2. Grandfather Charles Kyle who escaped westward into Tennessee where he joined a Union regiment and returned after the war to Salem and dared confront hostile former slave owners and rebels who had held him in bondage and fought against U.S. Colored Troops in the war. 3. Grand-Uncle Ellis Kyle who escaped slavery and joined a Union regiment, became a Buffalo soldier after the war, lived and worked in Ohio prior to returning to Salem as a pensioned veteran with his Civil War cavalry rifle given to William following his death in 1938. 4. Grand-Uncle Robert Wilkes Kyle who escaped northward with brother Ellis but fell from a bridge, broke his leg and was recaptured by confederate forces near Winchester, Virginia; beaten, tortured and returned as a slave to Salem; tried as a criminal in Salem County Court and sentenced to be publicly whipped each day for one year as a lesson to other slaves. Roanoke RiverThe Roanoke River is a river in southern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina in the United States, 410 mi (660 km) long.[1] A major river of the southeastern United States, it drains a largely rural area of the coastal plain from the eastern edge of the Appalachian Mountains southeast across the Piedmont to Albemarle Sound. An important river throughout the history of the United States, it was the site of early settlement in the Virginia Colony and the Carolina Colony. Most of its upper course in Virginia between the City of Roanoke and Clarksville is known as the Staunton River. It is impounded along much of its middle course to form a chain of reservoirs.

The river has its headwaters in the Blue Ridge Mountains in southwestern Virginia at Lafayette in Montgomery County where the North Fork and South Fork of the river merge. The North Fork, approximately 30 mi (50 km) long, rises between two mountain ridges and flows initially southwest, then loops back to the northeast. The South Fork, approximately 20 mi (30 km) long, rises in several streams in the mountains on the border of Floyd, Roanoke, and Montgomery counties and flows generally north, joining the North Fork from the south. The combined stream flows northeast between mountain ridges through the Roanoke Valley, approximately 10 mi (15 km) to Salem, then east through the city of Roanoke, emerging from a gorge in the Blue Ridge Mountains southeast of Roanoke and forming the boundary between Franklin and Bedford counties. The river flows generally east-southeast across the Piedmont of southern Virginia and enters northeastern North Carolina, passing north of Roanoke Rapids. The river then flows southeast in a zigzag course across the coastal plain and then briefly turns north as it enters Batchelor Bay on the western end Albemarle Sound. The river is impounded twice in succession in the Piedmont of southwestern Virginia downstream from Roanoke to form the Smith Mountain Lake and Leesville Lake reservoirs. Farther downstream in southern Mecklenburg County along the North Carolina border, the river is impounded to form the expansive Kerr Lake. In northeastern North Carolina, 3 mi (5 km) west of Roanoke Rapids, the river is impounded to form the Lake Gaston reservoir, which stretches upstream into Virginia to the John H. Kerr Dam. The Roanoke River was the homeland of various Native American tribes such as the Ocaneechi (today part of the Haliwa-Saponi). The deadly spring floods earned it the name "River of Death".[2] The river's lower course began to be settled by Virginians about the middle of the 17th century, in what was known as the Albemarle Settlements. The upper reaches of the Roanoke River were explored by fur trading parties sent by Abraham Wood in the late 17th century. The name "Roanoke" is said to have originated from an Algonquian word for shell "money". [3] In 1883, the small town of Big Lick on the river was selected as a major shops and terminal point for the new Norfolk and Western Railway to meet the Shenandoah Valley Railroad. Big Lick was renamed Roanoke for the river that bisected it, as the surrounding Roanoke County had been in 1838.[4]

A believer all his life, William believed Jesus, first and foremost, was a man of great courage who defied the Pharisee, Sadducee and Roman leaders all around him; and, likened him to the courageous Booker T. Washington for telling post-slavery African-Americans to "throw your buckets down where you are and draw water." Booker T. Washington had been born a slave in a slave cabin in Franklin County and some of his father's uncles claimed to have known him as a boy. It was a very common practice among slave owners before the Civil War to lease young bucks such as Adkins males for planned breeding purposes by other plantations such as the Burroughs family who had females they wished to generate offspring.

More often than not, in those days of woe for women and doctrine of "don't ask, don't tell" ... men did not know for certain whether offspring resulted from them and sometimes remarked "they say she had a baby by me." But rather true or not the African-American Adkins clan in Franklin, Pittsylvania and Roanoke Counties plus those in West Virginia, ... apparently admired the man born in cabin on right, and internalized much of his doctrinal advice about working with one's hands in opportunities like coal mining. Later in life, as a father, Bill noted to his sons that, ... "it took courage of men like Charles Kyle to escape slavery, courage to join the Union army and navy, courage to fight against the rebs, and courage to work in hard and often dangerous jobs like foundries, mills, railroading and coal mining." Most of the pleasant tales he knew about his grandfather Charles Kyle, he learned from his grandmother who rarely mentioned her dead husband's Civil War service, ... or that of her former slave owners and after-math of the war and disease that made many orphanages necessary for White children and lot of Black children in Virginia. Grandma Kyle avoided such topics. Her great-grandson William Thomas Atkins, Jr. recalls that his father William told him Grandma Adaline Kyle was freed from slavery when she was 18 years of age. If indeed, she was born in 1849 according to the U.S. Census track, then the release date would have been in 1867, two years after the Civil War ended. That has prompted us to perceive that she was likely a free-colored indentured servant under Virginia contract indenture laws that remained in effect until the 1870s. Those laws assured masters that indentured servants view themselves as little more than a privileged slave since they did not have personal liberty to move about without the master's written consent. She may have been born and raised as a slave to the Dillard family in Franklin County and in 1864 the Union forces that conquered southwest Virginia slave-owners required them to grant freedom for all slaves in accordance with the emancipation proclamation issued by President Lincoln on Jan 1, 1863. Indeed, slave owners did not give slaves their freedom without massive resistance, ... it was compelled by very bloody battles violently fought and lost by the confederate rebels. | Husband's Name |  | Peter Hairston DILLARD (AFN:XQV4-37) |  |  | Born: | Abt 1792 |  | Place: | Of, Horsepasture Crk, Henry, Virginia |  | Died: | 1867 |  | Place: | |  | Married: | Abt 1817 |  | Place: | Horsepasture Crk, Horsepasture, Henry, Virginia |  |  | Father: | | | | Mother: | |

| | Wife's Name |  | Elizabeth REDD (AFN:XQV6-CV) |  |  | Born: | 1792 |  | Place: | Of, Horsepasture Crk, Henry, Virginia |  | Died: | 1837 |  | Place: | |  | Married: | Abt 1817 |  | Place: | Horsepasture Crk, Horsepasture, Henry, Virginia |  |  | Father: | John REDD (AFN:XQV6-9J) | | | Mother: | Mrs-John REDD (AFN:XQV6-BP) |

| | Children |

| | | 1. | Sex | Name | | | | | M | Robert Hairston DILLARD (AFN:XQV4-LS) |  | | | | Born: | Abt 1818 |  | Place: | Of, Horsepasture Crk, Henry, Virginia | |

| | | 2. | Sex | Name | | | | | M | Overton Redd DILLARD (AFN:XQV6-D2) |  | | | | Born: | Abt 1822 |  | Place: | Of, Horsepasture Crk, Henry, Virginia |

| | | 3. | Sex | Name | | | | | F | Martha Ann DILLARD (AFN:XQV6-HK) |  | | | | Born: | Abt 1824 |  | Place: | Of, Horsepasture Crk, Henry, Virginia |

| | | 4. | Sex | Name | | | | | | F | Sarah DILLARD (AFN:XQV6-KW) |  | | | | Born: | Abt 1826 |  | Place: | Of, Horsepasture Crk, Henry, Virginia |

| | | 5. | Sex | Name | | | | | F | Mary DILLARD (AFN:XQV6-M8) |  | | | | Born: | Abt 1828 |  | Place: | Of, Horsepasture Crk, Henry, Virginia |

| | | 6. | Sex | Name | | | | | M | John Redd DILLARD (AFN:XQVB-J9) |  | | | | Born: | Abt 1830 |  | Place: | Of, , Henry, Virginia |

| | | 7. | Sex | Name | | | | | F | Lucy DILLARD (AFN:XQV6-PL) |  | | | | Born: | Abt 1830 |  | Place: | Of, Horsepasture Crk, Henry, Virginia |

| | | 8. | Sex | Name | | | | | M | George Penn DILLARD (AFN:XQV6-QR) |  | | | | Born: | Abt 1832 |  | Place: | Of, Horsepasture Crk, Henry, Virginia |

It appears that after the war, Adaline Frog met Charles Kyle who by then in 1866-1867 was no longer in the Union army that had made her freedom a reality. Without him and his kind of rebellion opportunities (affirmative actions) there is no doubt she would have remained a slave or indentured servant for life with her children and grandchildren like Willy raised up in the peculiar institution some folks obviously enjoyed. The Norfolk and Western Railway established rail links into points north, south and west of Roanoke County, Virginia, ... and subsequently numerous jobs for brakemen, firemen, and porters with the physical courage and stamina of Charles Kyle. Train locomotives were fueled by coal and the firemen on Norfolk and Western were usually African-Americans like Charles Kyle.

Prior to the invention of air-brakes by George Westinghouse and use on railroads like Norfolk and Western, ... each rail car in a train had to be individually braked by hand, and the brakemen on most trains were often young Black men for what was very strenuous and dangerous braking processes. As brakes were manually applied to each car, the brakeman had to normally dismount and run back to the next car for application of the braking system for its wheels. If the brakeman tripped or stumbled he could be seriously injured or lose limbs such as fingers, ... very common sights among Black men working or experienced on railways. While porter was a least dangerous category of work for African-American young men, it often required heavy lifting and constant movement on dry cargo, passenger and mail cars to prepare for loading and unloading at destinations. A long legacy of strugglePublished Jan 29, 2006 7:46 PM African Americans have been mining coal and fighting bosses for over 200 years. Slaves were working in coal mines around Richmond, Va. as early as 1760. During the Civil War, a thousand slaves dug coal for 22 companies in the “Richmond Basin.” Black miners were expected to load four or five tons of coal. Slaves able to fill this quota were fed supper. Those who couldn’t were whipped. Slavery in the mines didn’t end after the war in 1865. For decades prisoners convicted of “vagrancy” and “loitering” worked as virtual slaves for private outfits in Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee. From 1880 to 1904, 10 percent of Alabama’s state budget was paid by leasing prisoners to coal companies. African Americans accounted from 83 percent to 90 percent of these slave miners in Alabama. Sixty-nine percent of Tennessee prisoners digging coal in 1891 were Black. Some poor whites were railroaded to jail too. Conditions were horrendous in these convict mines. Nearly one out of ten prisoners died annually at the Tracy City, Tenn. mine operated by the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company (TCI). TCI was bought by United States Steel in 1907. USS continued to operate TCI’s mines in Alabama for another 20 years. Reparations are owed by USS and the JPMorgan/Chase Bank whose financial ancestor set-up this steel Goliath as the first billion-dollar corporation in 1900. Three hundred miners with guns freed prisoners at TCI’s Briceville, Tenn. facility on July 15, 1891. The following week 1,500 miners returned to free more prisoners. H.H. Schwartz of the Chattanooga Fed eration of Trades reported that “whites and Negroes are standing shoulder to shoulder” and armed with 840 rifles. James Knox, an African American convicted of passing a $30 bad check, was tortured to death by guards at Alabama’s Flat Top mine on Aug. 14, 1924 because he was unable to meet the mine’s daily ten-ton quota. The uproar over this murder finally forced Alabama to shut down its slave mines. On July 1, 1928, 499 Black prisoners singing the “Negro” spiritual, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”, turned in their lamps and picks for the last time. Black labor summoned to the mines. By 1930 there were over 55,000 Black coal miners. That year African Americans accounted for 53 percent of Alabama’s coal diggers. These Alabama miners went on strike in 1894, 1904 and 1908. Eleven thousand miners—75 percent of whom were Black—struck again from Sept. 7, 1920 to March 12, 1921. Among the Black leaders were J. F. Sorsby, United Mine Workers District 20 vice-president, and International organizers, William Prentice and George H. Edmunds. Despite bold tactics that included dynamiting a Southern Railroad train carrying scab coal, the strike was crushed by the National Guard. At least 16 people were killed. But the UMW came back to organize these mines in the 1930s during the Great Depression when militant struggles were being carried out by labor. Twenty-two thousand African Americans were employed in West Virginia’s mines in 1930. Black and white miners there fought side-by-side in the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike of 1913-14. The Black union man known as “Few Clothes” Dan Chain —portrayed by James Earl Jones in the powerful John Sayles film, “Matewan”—became legendary for his courage. The “mine wars” in Mingo and Logan counties from 1919 to 1921 produced the biggest armed confrontation in U.S. labor history. Logan County Sheriff Don Chaffin was paid $32,700 a year (worth about $400,000 today) by mine owners to keep out union organizers. Following the assassination of the pro-union sheriff Sid Hatfield on Aug. 1, 1921, 8,000 armed miners, one quarter of whom were Black, marched on Logan County. While ten union members were killed at Blair Mountain, one hundred of Chafflin’s mercenaries were slain. Army Gen. Billy Mitchell wanted to bomb the miners. Only the dispatch of 2,500 soldiers by President Warren G. Harding prevented the union’s victory. The mechanization of mines has wiped out 400,000 union jobs since 1950. Black workers were targeted first for dismissal. Just a few thousand African Americans are working in mines today. The 14 miners killed last month in West Virginia were white. Most of the people who drowned in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina were Black. Capitalist greed and the Bush administration are responsible for all of their deaths. Sources: Black Coal Miners in America by Ronald L. Lewis (The University Press of Kentucky, 1987) and Coal, Class and Color, Blacks in Southern West Virginia, 1915-1932 by Joe William Trotter, Jr. (University of Illinois Press, 1990). |

|

|

|