Mary Lee Brady, Ph.D.

| | Native American factoring into who are African-Americans is not only a pre-requisite into understanding American history but also digesting and understanding DNA test results for many curious souls that normally reflect East Asian and European heritage in addition to that of Africans.

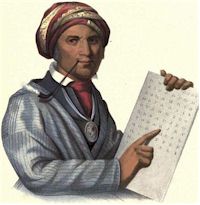

Sequoyah or George Guess (Gist)

Inventor of the Cherokee Alphabet The push across the Allegheny Mountains by American founders following the Revolutionary War encountered many Native settlements in places such as Western Virginia and Eastern Tennessee anxious for trade that often included African heritage slaves. Within a generation after the American Revolutionary War, slavery was well established among the Cherokee and Seminole natives and with it also came abolitionist sentiments among the slaves and freemen in the guise of organized religious missions, ... mainly Baptists. The links below offers insight into how so many African-Americans also have Native American heritage such as the Virginia originated Frog and Hill offspring of Cherokee Chief named Spring Frog who after relocation to Arkansas was a signer of the Treaty of 1817 by which the Cherokees ceded all their lands east of the Mississippi River to the United States Government. A special note is added that long before the Civil War began and ended, ... there was no love lost between young Black men who served in the Union Army and viewed the Cherokee as their enemies no different than other slave owners fighting to keep slavery alive against hopes for emancipation. CHEROKEE TREATY OF 1817 By time of the American Civil War, the Cherokee were divided on the question of slavery with about 10 percent of them owning and advocating the continuation of it, ... and like most Southern Whites the 90 percent who did not own slaves were encouraged by a vocal minority to believe it was good for them also. Many of the Cherokee sided with the slave holding Confederate Government including a famed Cherokee regiment best known for its massacre of African-American Union troops in a battle long remembered and revenged by Buffalo Soldiers following the Civil War. Cherokee soldiers in Texas were the last confederate rebels to surrender, ... on what African-Americans now celebrate as Juneteenth 1865. CHEROKEE SLAVE OWNERS

Scholars, particularly in recent decades among African-Americans have little interest or knowledge in functional geography, wars and reasons for conflicts such as the Civil War before and after that moved millions of men, women and children to better or worse. The fact of slave raiding, trading and use by men of any race (Black, White or Red) merely ascertains that a percentage of human beings (especially young men) were and are potentially capable of ruthless behavior when good young men do nothing to stop them. The Cherokee trail of tears was in part reaping what had been sowed with crying mothers and fathers of African heritage in places like Georgia, ... before President Andrew Jackson deemed them to be also inferior people and ceded their aspirations, hopes and dreams to White settlers. We have mixed emotions about the matters but hasten to note that as with the situation faced a century later in Europe, ... any previously assimilated group of people can be redefined as less than or more than others and with disastrous consequences reaping what their ancestors helped sow. TRAILS OF TEARS AND MEMORIES The Keetoowah Society and the Avocation of Religious Nationalism in the Cherokee Nation, 1855-1867

Chapter One Red, White, and Black in the Old South In truth, sacred bonds between blacks and Native Americans, bonds of blood and metaphysical kinship, cannot be documented solely by factual evidence confirming extensive interaction and intermingling -- they are also matters of the heart. These ties are best addressed by those who are not simply concerned with the cold data of history, but who have "history written in the hearts of our people" who then feel for history, not just because it offers facts but because it awakens and sustains connections, renews and nourishes current relations. Before the that which is in our hearts can be spoken, remembered with passion and love, we must discuss the myriad ways white supremacy works to impose forgetfulness, creating estrangement between red and black peoples, who though different lived as One. bell hooks

Black Looks: Race and Representation

IntroductionThe images that we have of the Southern history are forever shaped by the mythic: spanish moss clothed trees frame an ante-bellum plantation; stark images of black and white enveloped within a culture of racial polarization weave a narrative that has become our national image of the "Old South." Etchings burned so deep into our collective consciousness that they belie the very nature of the South itself, we are captivated by a false consciousness that disallows us from understanding the truly dynamic and complex nature of our own collective history. Even our understanding of nineteenth century and of the issues and individuals involved with the struggle for our national identity is so permeated with "myth-understanding" that it almost ceases to function in anything other than an ideological sense. The truth is that seldom are things as simple as they appear. Though it is little acknowledged, the history of the South is permanently colored by miscegenation. The issue of miscegenation (or "mongrelization" as it often called) has served as the rallying cry for generations of racists and hatemongerers, but it is as pervasive a fact in Southern society as almost any other social phenomenon. As early as 1630, the Governor of Virginia ordered citizen Hugh Davis to be "soundly whipped before an assembly of Negroes and others for abusing himself to the dishonor of God and shame of a Christian by defiling his body in lying with a Negro, which he was to acknowledge next Sabbath day." [1] Finally outlawed in Virginia in 1691, miscegenation had become a critical issue in colonial society: And for the prevention of that abominable mixture and spurious issue which hereafter may increase in this dominion, as well as by negroes, mulattoes, and Indians intermarrying with the English, or other white women, as by their unlawful accompanying with one another, Be it hereby enacted by the authorities aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That for the time to see, whatsoever English or other white man or woman being shall freely intermarry with a negro, mulatto, or Indian man or woman bond or free shall within three months after such marriage be banished and removed from this dominion forever, and that the justices of each respective countie within this dominion make it their particular care, that this act be put in effectual execution. [2] If one looks closely at the statement above, we find that the colonial Virginia fathers were equally concerned about intermarriage or relationships with "Indians" or "mulattos" as they were with those between colonials and African Americans. The presence of Native Americans and those with mixed blood were of seeming importance at this point in American history; later historians were the write these individuals out of history in order to perpetuate the black and white "master-narrative" that became the linchpin of Southern history. The role of the Native Americans in ante-bellum society, the presence and contributions of Africans to Native American societies, the important story of Afro-Indians in the Old South, and the issues of Native American slavery have been relegated to the back pages of history. In 1920, Carter G. Woodson observed that "one of the longest unwritten chapters of the history of the United States is that treating of the relations of the negroes and the Indians." [3] In nearly all discussions of Southern history, the presence of the multicultural nature of Southern society has been seldom explored. In the introduction to his chapter "The Indian and the Negro" in The Story of the Negro, Professor Booker T. Washington states, "The association of the negro with the Indian has been so intimate and varied on this continent, and the similarities as well as the differences of their fortunes and characters are so striking that I am tempted to enter at some length into a discussion of their relations of each to the other, and to the white man in this country." [4] The late William G. McLoughlin noted in his essay "Red, White, and Black in the ante-bellum South," that there is little discussion of the red, white and black because "two ideas at once are as much as the average American can hold in his head." [5] However, if we are to understand what happened to the Cherokee Nation in the years 1855-1867, we must explore the "red, white, and black" of the Old South. Myth-understanding and Early AmericaThere is little doubt that the first contact between Africans and Native Americans did not occur within the contexts of European colonial expansion in the early sixteenth century. Though most texts detailing red/black relations on the Southern frontier begin with Africans among the explorations of Spaniards De Allyon, De Leon, Cordoba, De Soto, and Narvaez, evidently contact was much older. It is an underappreciation of this often untold history of the deep relationship between Africans and Indians that lies at the root of modern misunderstanding of much of American history. Long before Christopher Columbus, Africans had been using favorable sea currents and small boats to come to the Americas. One of the reasons that Columbus was sent on his return voyage was "a report of the Indians of this Espanola who said that there had come to Espanola from the south and south-east, a black people who have the tops of their spears made of a metal which they call `guanin' (gold)." [6] The North Equatorial Current runs from West Africa to the Caribbean Islands and Southeastern United States; Thor Heyerdahl, in his Kon Tiki and Ra expeditions, proved that even the smallest boats could make this passage. [7] There is also ample evidence of pre-Columbian contact with Africans in a variety of settings in Mesoamerica. The African characteristics of Olmec sculptures, similarities between African pyramids and reed boats and their counterparts in Mesoamerica, and pictographic/linguistic similarities between Northern African and Muscogean cultures are all evidence of ancient contact. [8] Upon observing the Olmec sculptures in 1869, Dr. Jose Melgar y Serrana reported "As a work of art, it is without exaggeration a magnificent sculpture, but what astonished me was the Ethiopic type represented. I reflect that there had undoubtedly been Negroes in this country." [9] Dr. Leo Wiener proposed that African traders from Guinea founded a colony near Mexico City from which they exerted a cultural and commercial influence extending north to Canada and south to Peru. He also suggests that Native American ancient cultures, including the Maya, Aztec, and Inca civilizations, were directly or indirectly of African origins. [10] Historians and scientists from Augustus Le Plongeon in the nineteenth century to Barry Fell in the latter half of the twentieth century have asserted African contact with ancient America. [11] Whatever the truth is, it is certain that it was along the coastal rim of the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico where the early explorers encountered most African-Indians and tri-racial mixtures. [12] Taking the African presence in ancient America seriously causes us to reframe our understanding of the relationship between African Americans and Native Americans in the Southeastern United States. What are the implications of this research for understanding Native American attitudes regarding race; moreover, what are the possibilities of African influence in the development of the temple mound culture in the Southeastern United States? Does this historic background explain the ease in which in which Africans learned to speak and translate indigenous languages and the ready assimilation of runaway slaves into Native American communities? It is not the purpose of this paper to fully explore the meaning of this critically underexplored phenomena, but to simply offer up the possibility of a thicker description of southeastern culture. [13] Modern historians believe that the first Africans to be encountered by Native Americans were those who accompanied the early Spanish explorations of the Southeastern United States. Estavanico, "an Arabian black, native of Acamor," who accompanied Narvaez into Florida distinguished himself by his linguistic ability and "was in constant conversation" with the Indians. [14] In 1540, Hernando de Soto encountered the Cherokee and kidnapped the Lady of Cofitachequi, a prominent Cherokee leader. Escaping from De Soto, she returned home with an African slave belonging to one of De Soto's officers and "they lived together as man and wife." [15] Black slaves also played a critical role in Luis Vazquez de Ayllon's aborted colony in South Carolina; a slave revolt occurred in the colony and many of the African slaves fled to live among the Cherokee. [16] It is important to understand the purpose of these early Spanish explorations in the Southeast. Ponce de Leon's 1512 patent from the Spanish authorities provided that any Indians that he might discover in the Americas should be divided among the members of his expedition that they should "derive whatever advantage might be secured thereby." [17] De Ayllon's 1523 cedula authorized him to "purchase prisoners of war held as slaves held by the natives, to employ them on his farms and export them as he saw fit, without the payment of any duty whatsoever upon them." [18] When De Soto landed in Florida with his soldiers in 1539, he brought with him blood-hounds, chains, and iron collars for the acquisition and exportation of Indian slaves. Hundreds of men women and children were captured by de Soto and transported to the coasts for shipment to the Caribbean and to Spain. [19] A Cherokee from Oklahoma remembered his father's tale of the Spanish slave trade, "At an early state the Spanish engaged in the slave trade on this continent and in so doing kidnapped hundreds of thousands of the Indians from the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts to work their mines in the West Indies." [20] Slavery as a phenomenon was not unknown to the Cherokee Nation or to Native Americans. However, it is distinctively different in both its content and its context as that which was practiced by the European. Rudi Halliburton in Red Over Black, his extensive work on slavery in the Cherokee Nation, concludes that "slavery, as an institution, did not exist among the Cherokees before the arrival or Europeans." [21] Booker T. Washington concurs, "The Indians who first met the white man on his continent do not seem to have held slaves until they first learned to do so from him." [22] The Cherokee atsi nahtsa'i, or "one who is owned," were individuals captured or obtained through warfare with neighboring peoples and often given to clans who lost members in warfare. [23] To the extent that these individuals existed outside of the clan structure, they were in essence "outsiders" who lived on the periphery of Cherokee society. It was up to the clan-mothers, or "beloved women" of the Nation to decide upon the fate of these individuals. [24] If they accepted these "outsiders" as replacements for those individuals who had lost their lives in battle, these individuals became members of the clan and thus the nation. [25] If the "outsiders" were not accepted into the clan, then they served as the "other" in promoting clan self-understanding and solidarity. [26] There was not a race-based understanding of "difference" within Native American cultures as that which had come to exist within the European mind over the hundred years following the discovery of the New World. Race as an identifying component in interaction did not exist within the traditional nations of the early Americas; into the nineteenth century the Cherokee were noted for their cultural accommodation. [27] William McLoughlin stressed the importance of clan relationships or larger collective identities (e.g., Ani-Yunwiya, Ani-Tsalagi, Ani-Kituhwagi) within indigenous nations as the critical components in their interactions with outsiders; race was not considered a critical element in perception or hostility. [28] In her pivotal work Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society 1540-1866, Theda Perdue states that the Cherokee regarded Africans they encountered "simply as other human beings," and, "since the concept of race did not exist among Indians and since the Cherokees nearly always encountered Africans in the company of Europeans, one supposes that the Cherokee equated the two and failed to distinguish sharply between the races." [29] Kenneth Wiggins Porter, an African American historian, concurs with this conclusion: [we have] "no evidence that the northern Indian made any distinction between Negro and white on the basis of skin color, at least, not in the early period and when uninfluenced by white settlers." [30] However, racism and religious intolerance were critical components in the European dispossession and enslavement of Native Americans in the colonial period. Originating in the Aristotelian concept of natural rights, the concept of white supremacy as it developed in the sixteenth century ran along these lines: Those, therefore, who are as much inferior to others as are the body to the soul and beasts to men, are by nature slaves. He is by nature born slave who...shares in reason to the extent of apprehending it without possessing it. [31] Juan Gines De Sepulveda, in his disputation with Bartholomeo de las Casas in Vallodolid in 1555, argued the superiority of the Spaniard to the indigenous people: In wisdom, skill, virtue and humanity, these people are as inferior to the Spaniards as children are to adults and women to men; there is a great a difference between savagery and forebearance, between violence and moderation, almost -- I am inclined to say -- as between monkeys and men. [32] Las Casas, "Champion of the Indians," argued against this ideology by asserting: Aristotle, farewell! From Christ, the eternal truth, we have the commandment `You must love your neighbor as yourself.' Although he was a profound philosopher, Aristotle was not worthy to be captured in the chase so that he could come to God through knowledge of true faith." [33] ...the natural rules and laws and rights of men are common to all nations, Christians and gentile, and whatever their sect, law, state, color, and condition, without and difference." [34] Las Casas won the day in Valladolid, but the moral argument of Las Casas was soon swept aside by a European continent facing a vast world with countless treasures inhabited by a people who could, themselves, become a commodity in the open market. [35] What was originally the "black legend" of Spanish ethnocentrism and genocidal cruelty spread quickly throughout Europe as political, economic, and religious sentiment fueled colonial expansion. [36] Though initially shocked by Sir John Hawkins' first slavery venture in 1562-1563, Queen Elizabeth quickly changed her mind, "not only did she forgive him but she became a shareholder in his second slaving voyage." [37] By the middle of the seventeenth century, the traffic in slaves from Europe, Africa, and the Americas became a mainstay of the colonial economic enterprise. Behind the mercantile enterprise was a moral sanction of a pervasive ideology: No slaughter was impermissible, no lie dishonorable, no breach of trust shameful, if it advantaged the champions of true religion. In the gradual transitions from religious conceptions to racial conceptions, the gulf between persons calling themselves Christian and the other persons, whom they called heathens, translated smoothly into the chasm between whites and coloreds. The law of moral obligation sanctioned behavior on only one side of that chasm... the Christian Caucasians of Europe are not only holy and white but also civilized, while the pigmented heathens of distant lands are not only idolatrous and dark but savage. Thus the absolutes of predator and prey have been preserved, and the grandeur of invasion and massacre has kept its sanguinary radiance. [38]

|

http://www.us-data.org/us/minges/keetood2.html |